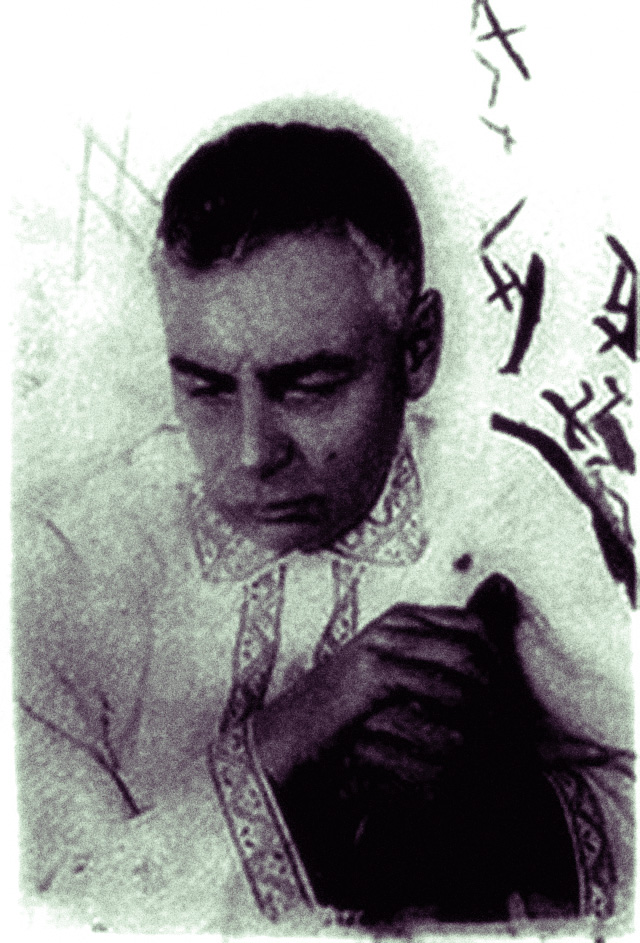

Na de Russische revolutie werd Alexandr Voronsky een van de vooraanstaande literatuurcritici van de Sovjet-Unie. Na de dood van Lenin koos hij de kant van Trotski in diens strijd tegen Stalin. Hij werd ervoor geëxecuteerd. In 1998 verscheen een keuze uit zijn werk, een Engelse vertaling van zesentwintig artikelen, essays en redevoeringen die Voronsky tussen 1911 en 1936 geschreven heeft. (1) De bundel heet Art as the Cognition of Life, wat wil zeggen dat kunst ons iets over ’t leven kan leren. Voronsky legt ons uit hoe we dat aan boord moeten leggen. Voronsky is een marxist. Hem interesseert de vraag in hoeverre gevoelens, gedachten en stemmingen die in een literair werk uitgedrukt worden, rijmen met de belangen van een sociale klasse. Ook vraagt hij zich af welke rol concrete artistieke doctrines in de sociale strijd spelen.

Na de Russische revolutie werd Alexandr Voronsky een van de vooraanstaande literatuurcritici van de Sovjet-Unie. Na de dood van Lenin koos hij de kant van Trotski in diens strijd tegen Stalin. Hij werd ervoor geëxecuteerd. In 1998 verscheen een keuze uit zijn werk, een Engelse vertaling van zesentwintig artikelen, essays en redevoeringen die Voronsky tussen 1911 en 1936 geschreven heeft. (1) De bundel heet Art as the Cognition of Life, wat wil zeggen dat kunst ons iets over ’t leven kan leren. Voronsky legt ons uit hoe we dat aan boord moeten leggen. Voronsky is een marxist. Hem interesseert de vraag in hoeverre gevoelens, gedachten en stemmingen die in een literair werk uitgedrukt worden, rijmen met de belangen van een sociale klasse. Ook vraagt hij zich af welke rol concrete artistieke doctrines in de sociale strijd spelen.

Sociologisch onderzoek, zo stelt Voronsky, volstaat echter niet om een literair werk te waarderen. Zo’n onderzoek mag dan voorop staan, het is niet compleet. Aan literatuur hangt immers een on(der)bewustkantje vast; ze komt in belangrijke mate intuïtief tot stand: “Intuition is our active unconscious. Intuitive truths are authentic and indisputable; they require no logical verification and frequently cannot be verified by logical means precisely because they undergo preliminary development in the subconscious realm of our life and then reveal themselves immediately, suddenly and unexpectedly in our consciousness, as if they were independent of our “ego,” and not subject to its preliminary work”.

Daarom moet de criticus tegelijk nagaan, zegt Voronsky, in hoeverre een boek “esthetisch waar” is. Dat laatste is een merkwaardig begrip en Voronsky moet veel moeite doen om het uitgelegd te krijgen: “For the artist thinks in images: the image must be artistically true, i.e., it must correspond to the nature of what is portrayed. In this lies perfection and beauty in the work of an artist.”

Elders zegt hij: “The aesthetic evaluation is made as a result of the sensation that the artist has correctly, comprehensibly and accurately constructed his images for us.’ En ten slotte: ‘Our mind takes an active part in the creation of the image, but an even greater part in its creation belongs to unconscious creative work. The image is aesthetically evaluated, and the aesthetic evaluation is not devoid of rationalistic elements, but in its underlying core it is also intuitive. Therefore there is no foundation to say that the definition of art as thinking with the help of images suffers from narrow rationalism. Only such a definition gives a satisfactory answer, from the standpoint of Marxism, to the question: what is artistic truth?”

Pffffffff, ik probeer samen te vatten. De literaire criticus, zegt Voronsky, onderzoekt hoe sociale strijd en klassenbelangen in de literatuur tot uiting komen, er rekening mee houdend dat de auteur in belangrijke mate geleid wordt door onder- of onbewuste mechanismen die hem juist daardoor een aparte plaats bezorgen.

Nadat ik dat allemaal gelezen heb, vraag ik me af of dit niet een ingewikkelde manier is om iets heel eenvoudigs te zeggen. Maar kijk, misschien maakt Sartre het me duidelijk waar hij eenvoudigweg zegt: “Valéry is een kleinburgerlijke intellectueel, daar valt niet aan te twijfelen. Maar niet elke kleinburgerlijke intellectueel is Valéry”.

Aleksandr K. Voronsky, Art as the Cognition of Life: Selected Writings, 1911–1936, trans. and ed. Frederick S. Choate (Mehring Books, 1998), 190 pagina’s.

Dit artikel verscheen oorspronkelijk op De Laatste Vuurtorenwachter.